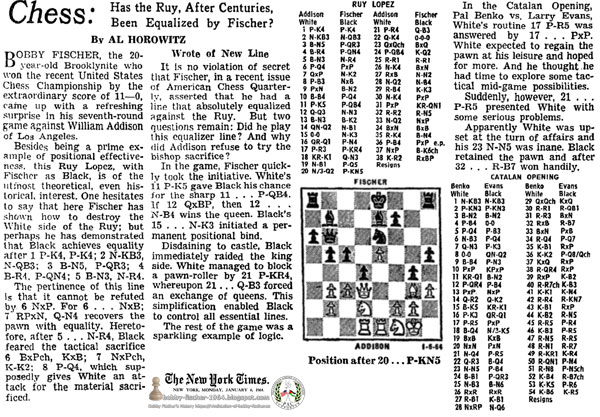

New York Times, New York, New York, Monday, January 06, 1964 - Page 44

Chess: Has the Ruy, After Centuries Been Equalized by Fischer?

Bobby Fischer, the 20-year-old Brooklynite who won the recent United States Chess Championship by the extraordinary score of 11—0, came up with a refreshing surprise in his seventh-round game against William Addison of Los Angeles.

Besides being a prime example of position effectiveness, this Ruy Lopez, with Fischer as Black, is of the utmost theoretical, even historical interest. One hesitates to say that here Fischer has shown how to destroy the White side of the Ruy; but perhaps he has demonstrated that Black achieves equality after 1 P-K4, P-PK4; 2 N-NB3, N-QB3; 3 B-N5, P-QR3; 4 B-R4,P-QN4; 5 B-N3, N-R4.

The pertinence of this line is that it cannot be refuted by 6 NxP. For 6 . . . NxB; 7 PRxN, Q-N4 recovers the pawn with equality. Heretofore, after 5 . . . N-R4, Black feared the tactical sacrifice 6 BxPch, KxB; 7 NxPch, K-K2; 8 P-Q4, which supposedly gives White an attack for the material sacrificed.

Wrote of New Line

It is no violation of secret that Fischer, in a recent issue of American Chess Quarterly, asserted that he had a line that absolutely equalized against the Ruy. But two questions remain: Did he play this equalizer line? And why did Addison refuse to try the bishop sacrifice?

In the game, Fischer quickly took the initiative. White's 11 P-K5 gave Black his chance for the sharp 11 ... P-QB4. If 12 QxBP, then 12...N-B4 wins the queen. Black's ... N-K3 initiated a permanent positional bind.

Disdaining to castle, Black immediately raided the king side. White managed to block a pawn-roller by 21 P-KR4, whereupon 21 ... Q-B3 forced an exchange of queens. This simplification enabled Black to control all essential lines.

The rest of the game was a sparkling example of logic.